Ancient Origins

In ancient times, Yaquis were living in family groups along the Yaqui River (Yoem Vatwe) north to the Gila River, where they gathered wild desert foods, hunted game, and cultivated corn, beans, and squash. Yaquis traded local foods, furs, shells, salt, and other goods with many indigenous groups. Yaquis traveled extensively in pre-Columbian times and sometimes settled among other Native groups like the Zuni.

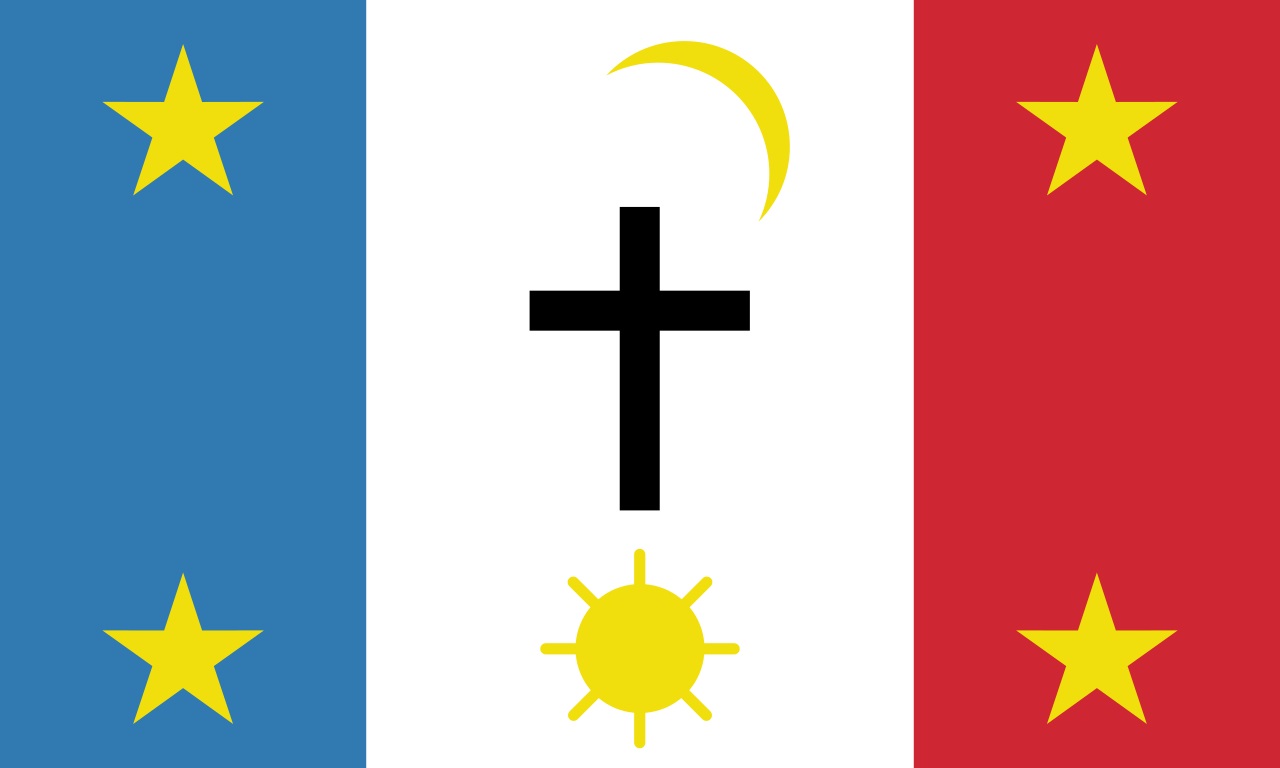

The Yaqui peoples homelands consisted of several towns in the Yaqui River delta near the Sea of Cortez in Sonora, Mexico. The Jesuits established missions here among the Yaqui by the 19th century. A syncretic Catholic-Native religion developed where Yaquis incorporated Catholic rituals, saints, and teachings into their existing indigenous worldview.

After contact with non-Natives after the Spanish arrival in the 1500s, the Yaquis came into an almost constant conflict with Spanish colonists and the later Mexican republic, a period known as the Yaqui Wars, which ended in 1929. The 400 years of wars with the occupiers sent many Yaquis north from Mexico back into Arizona, and the southwestern United States.

Refugees and Early Communities in Arizona

The Pascua Yaquis and other Yaquis in Arizona descend from refugees who fled Mexico between 1887 and 1910. During these years the Mexican government attempted to destroy the Yaqui Nation, via warfare, occupation, and forced deportation of Yaquis to virtual slavery in the Yucatan. Yaqui refugees established Yaqui barrios at Pacua and Barrio Libre in Tucson, at Marana, and at Guadalupe and Scottsdale near Phoenix.

By the 1940s there were approximately 2,500 Yaquis in Arizona. Most worked as migrant farm laborers. This seasonal work melded well with the off-season when Yaquis would plan and carry out complex religious ceremonials that took months to complete. In Arizona, the Yaqui communities re-established traditional ceremonies, most importantly, the Lenten ceremonies that reenact the passion and resurrection of Jesus Christ. The Pascua community is named after "Pascua," Easter in Spanish. The various Yaqui communities established modest Catholic churches. At Pascua the church was named San Ignacio de Loyola. The Easter ceremonies featured the Yaqui deer dancer, the most enduring symbol of the Yaquis in America. The Pascua Yaquis maintained other aspects of the syncretic Jesuit-Yaqui religious traditions and offices as well.[3]: 80-83

Building Community in Tucson

After fleeing to Arizona, most Yaquis lived in dire poverty, squatting on open lands most often near railroad lines. In 1923, a retired teacher and humanitarian, Thamar Richey, successfully lobbied Tucson to establish a public school for Yaqui children. A realtor donated land for a new subdivision named Barrio Pascua near downtown. This community became a center of Yaqui life in Arizona.

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, there was an effort to deport the foreign-national Yaquis back to Mexico. This effort failed largely because the State Department determined their safety could not be ensured. To protect the Yaquis, Thamar Richey in 1935 established a civic-minded committee that included University of Arizona President H.L. Shantz, Anthropology Professor Edward Holland Spicer, and Arizona's first congresswoman Isabella Greenway. Spicer, whose work on the Pascua Yaquis would establish him as one of the nation's leading anthropologists, and the others contacted the Bureau of Indian Affairs to aid the group. Issues of their Mexican origins clouded this effort. As this was during the landmark Indian New Deal when Commissioner of Indian Affairs John Collier was attempting to aid indigenous groups that for decades had faced federal assaults on their lands and cultures, at one point he offered a solution: the Yaquis could relocate to the Colorado River Reservation in far western Arizona. Ultimately this plan failed because of finances and nationality questions.[3]: 83-86

Post-War Advocacy and Leadership

After World War II, a Yaqui veteran, Anselmo Valencia, returned to Pascua vowing to improve life for his people. He came home determined to fight for his people's rights as American citizens and indigenous Americans. He became head of the religious caballeros society. In 1955, Valencia established the San Ignacio Club to work for community betterment at Pascua.

Around this time a University of Arizona anthropology student, Muriel Thayer Painter, began to study the Pascua Yaquis, vowing to aid the struggling group. Residents of Pascua increasingly had lost their lots to tax foreclosures and other economic issues. A study found that most homes had no running water, indoor plumbing, or electricity. Valencia, Spicer, and Painter established the Committee for Pascua Community Housing in the early 1960s to improve housing conditions in the neighborhood.

In 1962 while collecting wild herbs in the desert southwest of Tucson, Valencia had a vision that his people would one day relocate there. To accomplish this, Valencia, Spicer, and Geronimo Estrella spearheaded the creation of the Pascua Yaqui Land Development Project, with membership that included Yaquis Felipa Suarez, Gloria Suarez, Joaquina Garcia, and Raul Silvas. The group contacted Congressman Mo Udall for federal help in 1962.[3]: 86-91

Establishment of Modern Tribal Government

At the urging of Ned Spicer, in 1962 the Yaquis formed the Pascua Yaqui Association (PYA) as a non-profit corporation to receive funds and to deal with federal officials. The PYA evolved into the modern Pascua Yaqui tribal government. The PYA was a quasi-tribal government that worked with Congressman Mo Udall to prepare legislation to transfer federal land for the new Yaqui community Valencia had envisioned on the outskirts of Tucson.

Because so many members of Congress were opposed to establishing a new tribal-federal relationship with the Yaquis during the "Termination Era" that lasted until the 1960s, language was inserted in the land transfer bill that prohibited the Pascua Yaqui from being eligible for Bureau of Indian Affair's services or benefits that flowed from tribal acknowledgment.[3]: 91-98